A Daughter’s Remembrance and Dedication

L. Martina Young

Dad was a walker. Open to every person he met along his way, he’d greet each one with a “Hello,” or “How are you doing today,” all with a smile and a gladdened eye. It is a lesson I carry with me today as I too have become a walker—choosing to own a car no more and to take in my world by foot. Just today, a white-haired elderly man who I often pass on the street corner remarked, “Your smile is exhilarating!”

Dad was seventy-six when he died. The year, 2002. In 1995 he’d had a severe stroke. It was not his first. Dad had also been taking Laetrile since 1994 which had brought his prostate cancer into remission after an initial three-week stay at Contreras Hospital in Mexico. (Then, I had arranged week-long stays with him—my brother, myself, and Dad’s then love-woman—so that he would have loved ones with him over the entire three weeks.) With his hyper-tension condition, dad had had a minor stroke in his fifties—if there is such a thing as a ‘minor stroke.’ He called me from Los Angeles County Hospital to bring him a few things and generally to assure me that he would be alright. When Dad had the big one in 1995, I lived with him in grand-dad George’s house in Oxnard, California, on Juanita Avenue,—in what brother David has musically lyricize’d, “In My Father’s Father’s House.” A friend of his had called me from the barrio. They’d been together when Dad fell ill—Dad was his go-to on issues of politics and social activism for black, brown, and red folk.

As is my natural inclination, I tended to Dad with the observed indigenous healing practices for body and mind: rose water; gentle talk; herbs and nutritious foodstuffs; bath soaks; and daily camaraderie. Before Dad died he lamented: “I’m sorry. I have left you nothing.” “But Daddy!” I said—“you’ve left me everything. Everything a daughter of this time and of this land needs to be who she is meant to be. I am the richer with you as my father. You should know: I want for nothing more. I love you.

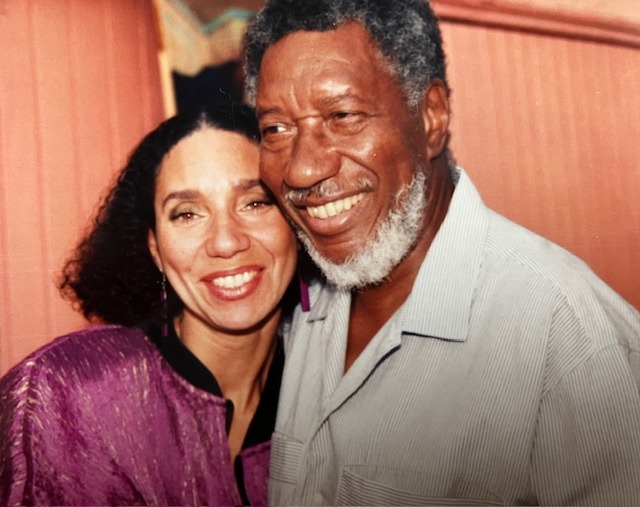

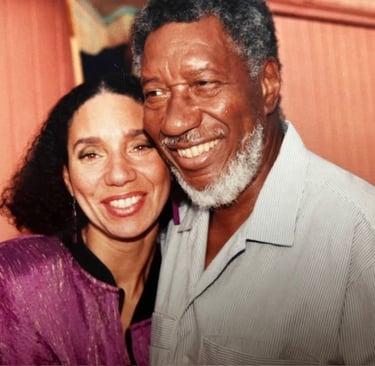

"Family Portrait: Mother Martina, Daughter Linda Martina, Son David Allen" | Family Heirloom

Dad’s T-Shirts | Family Heirloom

I am my daddy’s daughter. His first born. And yes, I was the apple of his eye. But this is also to say that my brother, David, daddy’s second born, too was the apple of his eye. As were all of his lineage: grandson Jarrett Allen; grandniece Zoey Kenya; and, though he did not live to see his great-grandson, Lachlan Clay, his namesake. All were equally loved.

But I speak now for myself, from the resonances in my soul-life that are both ground and beacon for living a life in this world at this time. I am seventy. For this milestone, I was able to gather family and friends to celebrate together at a favorite neighborhood and my last California residence: the Pacific Ocean of Marina del Rey and Venice Beach—though now dramatically different from the time I lived there. The same neighborhood, Venice and Santa Monica in particular, was also dad’s favorite place of residence—where he lived some of his most happy days and where was most content. Dad also experienced a deep sense of contentment during his years in Ecuador as an artist in the Peace Corps. In fact, he chose to serve an additional year beyond the standard two-year residency commitment. Bilingual and an artist of the people, dad was deeply loved by members of his Ecuadorian community, people I had the rich joy of meeting and spending time with during my month-long stay with dad in the winter of 1980.